- |

User Links

Hymns of the Holy Eastern Church: translated from the service books with introductory chapters on the history, doctrine, and worship of the church

HYMNS

|

PRINTED BY

ALEXANDER GARDNER, PAISLEY

PREFACE

The generous reception given to a former

series of renderings of Hymns from the Office Books of the Greek

Church

No apology is needed for this additional volume on a subject too little known, the contents of which are an earnest attempt to acquaint our people still further with the valuable praise literature of the Eastern Church.

We are still far from realising the unity of

the Church of Christ in the world, when that

section of it which is historically nearest The

Christ--which joins hands with Him and

Of the forty-six pieces in this volume, forty-two appear for the first time in English verse. While leaving critics to pass their verdict on the value of the work, the translator can yet justly claim to have made a substantial addition to our English hymnody from Eastern sources.

The renderings have all been made from the Service Books, the edition used being the one printed at Venice,--with the exception of the Triodion, which belongs to the Athens edition.

To enable any who are interested in the subject, and who may have access to the Service Books, to compare the renderings with the original text, the title of the book, and the number of the page where it can be seen, are given in each case.

The Introductory chapters on the History, Sacraments, and Worship of the Church, are given in the hope that they may be the means of removing prejudices and misconceptions, and of awakening some degree of interest in the Eastern Church.

For much of the information contained in these chapters the translator is indebted, among other works, to Neale's History of the Holy Eastern Church, Stanley's History of the Eastern Church, King's Rites and Ceremonies of the Greek Church, and Gibbon's Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire. But many of the facts were collected a few years ago during a residence in the East.

J. B.

Trinity Manse,

Portpatrick, Nov. 1, 1902.

GREEK INDEX

- PAGE

- ἐν τῷ θλίβεσθαί με, εἰσάκουσόν μου τῶν ὀδυνῶν--(Antiphon), 71

- εἰς τὰ ὄρη ψυχὴ ἀρθῶμεν·--(Antiphon), 72

- ἐπὶ τοῖς εἰρηκόσι μοὶ·--(Antiphon), 73

- ἐξεγερθέντες τοῦ ὕπνου, προσπίπτομέν σοι--(Troparia), 74

- ταχεῖαν καὶ σταθηρὰν δίδου παραμυθίαν τοῖς δούλοις σου, Ἰησοῦ--(Troparion), 76

- ψυχή μου! ψυχή μου! ἀνάστα, τί καθεύδεις;--(Kontakion-Automelon), 78

- ἡ βασιλεία σου, Χριστὲ ὁ Θεὸς--(Sticheron Idiomelon), 79

- ἡ γέννησίς σου Χριστὲ ὁ Θεὸς ἡμῶν--(Apolutikion), 81

- ὅτε ἥξεις ὁ Θεὸς ἐν μυριάσι καὶ χιλιάσι--(Troparia), 82

- ὁ κύριος ἔρχηται--(Troparia), 83

- ἠχήσουσι σάλπιγγες--(Stichera), 84

- βίβλοι ἀνοιγήσονται--(Stichera), 85

- δεῦρο ψυχή μου ἀθλία--(Ode), 86

- ὁ δεσπόζων τῶν αἰώνων πάντων κύριος--(Ode), 88

- τὰ πλήθη τῶν πεπαγμένων μοι δεινῶν--(Sticheron), 90

- τίς αὗτος Σωτὴρ, ὁ ἐξ Ἑδώμ--(Troparia), 91

- ἔφριξε γῆ, ἀπεστράφη ἥλιος--(Troparia), 92

- ὁ βουλήσει ἅπαντα ποιῶν--(Troparia), 93

- ὑμνοῦμεν σου Χριστὲ, τὸ σωτήριον πάθος--(Stichera), 95

- ἀναστάσεως ἡμέρα, καὶ λαμπρυνθῶμεν τῇ πανηγύρει--(Sticheron), 97

- κύριε, ἐσφραγισμένου σοῦ τάφου--(Stichera), 98

- τῷ πάθει σου, Χριστὲ, παθῶν ἠλευθερώθημεν--(Stichera), 100

- τοῦ λίθου σφραγισθέντος ὑπὸ τῶν Ἰουδαίων--(Apolutikion), 102

- ἑσπερινὴν προσκύνησιν--(Stichera), 104

- ὁ κύριος ἀνελήφθη εἰς οὐρανοὺς--(Stichera), 106

- ὡς αἱ τάξεις νῦν τῶν ἀγγέλων ἐν οὐρανῷ--(Hymn to The Trinity), 107

- τὰς ἄνω Δυνάμεις μιμούμενοι οἱ ἐπὶ γῆς--(Hymn to The Trinity), 109

- ὑμνῳδίας ὁ καιρὸς, καὶ δεήσεως ὥρα·--(Hymn to The Trinity), 111

- σὺ μόνος ὢν θαυμαστὸς, καὶ ἐν ἀνθρώποις τοῖς πιστοῖς ἵλεως--(Ode), 113

- ὡς θεῖος ποταμὸς, τοῦ ἐλέους ὑπάρχων--(Kathisma), 114

- σταθερῶς τοὺς ἀγῶνας ἐπιδειξάμενοι--(Ode), 115

- ποία τοῦ βίου τρυφὴ διαμένει λύπης ἀμέτοχος;--(Idiomela), 116

- ὁρῶντές με ἄφωνον καὶ ἄπνουν προκείμενον.--(Sticheron), 118

- ὢ τίς μὴ θρηνήσει τέκνον μου--(Stichera), 120

- παράδεισε πάντιμε, τὸ ὡραιότατον κάλλος--(Stichera), 121

- ἀληθῶς ματαιότης τὰ σύμπαντα--(Cento), 125

INTRODUCTION

I

The Eastern Church is little known in the West, and it would seem that there is not much desire on our part to alter that condition of things. As the Eastern Hemisphere is separated from the Western by the Ural and Carpathian ranges, so is Eastern Christendom separated from Western Christendom, and more effectually, by the mountain barriers which our ignorance, prejudice, and indifference have set up. But it is well to remember the German proverb, Behind the mountains are also people, and that the people who are behind those mountains which have been the growth of centuries, form nearly one-fourth of the followers of the Faith of Christ, or about one hundred million souls.

The causes which have led to this indifference

on the part of the West towards the

(I.) The first of these is the inherent peculiarity of temperament, which finds its expression in habits of thought, and modes of action, in the East, against which the spirit of the West frets, and for which it has neither sympathy nor toleration. The quiet, meditative restfulness of the East--its satisfaction with past attainment in the matter of Doctrine and Worship, its wistful retrospective gaze upon magnificent accomplishment, which the experience of centuries of trial has only intensified, are totally alien to the active, speculative, hopeful spirit of the West. Attainment is the boast of the East, and in that it rests content. Progress, achievement, is the craze of the West. Those temperaments, so obviously diverse, have for long parted company.

(II.) The other is the great Roman

Church. Inspired with that spirit which

commends itself to the Western mind--its

activity, its aptitude to fit itself to the

ever-changing circumstances of the times, its

But the Eastern Church deserves better at our hands than to be thus forgotten. In these days of unrest, when men's minds are unsettled on so many questions, a strange, alluring calm pervades our spirit when we overtop the barriers and look down upon the peace and quiet of Eastern Christendom. There, in all her pristine simplicity and attractiveness, as in the golden days of the Empire, as in the fierce conflict of the early middle ages when John of Damascus whetted the sword for the conflict, so now under the misrule and tyranny of the Turk, she holds in quiet restfulness the simple faith committed to her by the Apostles and Fathers, the same Church now as then.

Do we forget that the Fathers of the

Eastern Church formulated our doctrines,

and shaped our Creed, guarding it in

every item with jealous care? Do we forget

that the Churches founded by the

apostles in Syria and Asia Minor still hold

by the apostolic doctrine, and are parts of

Such thoughts should incline us sympathetically towards the Church of the East, and enable us to overtop the barriers which have been raised by incidents of history and unfounded prejudices and differences of temperament, which in no way affect the fact of our indebtedness to that Church, and consequently her claim upon our intelligent interest.

But we are told that, after all, there is

little difference between the Roman Church

and the Greek Church--that the abuses of

the one are the abuses of the other. That,

we shall see shortly, is not the case. And

we are told, too, that the Greek Church is a

dead Church, and without missionary zeal.

How a Church that has stretched out its

hands to the farthest east, bestowing the

blessings of the Gospel upon Tartar and

Indian; southward, planting the Cross in

Arabia, Persia, and Egypt; northward, diffusing

light to the limits of Siberia, can be

termed a non-missionary Church, is difficult

to understand. How a Church that has

fought hand to hand with idolatry, not only

in the early ages when her spirit was young,

Prior to the great schism of 1054, when the See of Rome separated from the East, and the Pope excommunicated Michael Cerularius, Patriarch of Constantinople, in East and West, Christendom was practically one. The causes which led to that separation, which was fraught with momentous and far-reaching issues for Christianity, may be briefly referred to. They had their beginnings in the far past.

The building of Constantinople in A.D. 330 by the Emperor Constantine on the site of the ancient Byzantium, and the subsequent transference of the seat of government to that city, were in reality the prime causes leading to that disagreement and alienation, which grew in intensity and broadened, till they reached the point of entire separation.

Prior to that event, Byzantium was but

The responsibility for the great schism

undoubtedly lies with Rome, and that should

be remembered for all time. The introduction

of Filioque into the Creed was a

proceeding by no means called for. Christians

could quite well have lived and worked

II

Prior to the fall of the Empire in the

middle of the fifteenth century, the Greek

Church comprised within her borders,

Greece, Illyricum (Dalmatia), the islands

of the Archipelago; Russia; Asia Minor,

Syria, and Palestine; Egypt, Nubia, and

Abyssinia; Arabia, Persia, and Mesopotamia.

After that disaster she fell into a

dependent condition in those territories

secured by the Turk. In the eighteenth

century Russia claimed separation from

Constantinople, and has been governed

since by a Holy Synod; and when the new

kingdom of Greece was established in the

early part of last century, the Church there,

in like manner, claimed a distinct organisation.

Scattered portions of the Church,

chiefly in Hungary, Servia, Bosnia, Bulgaria,

At the present time, the Eastern Church may be thus grouped--

- I. The Greek Church proper.

- II. The Heretical Churches.

- III. The Russian Church.

I. The Greek Church comprises those peoples who speak the Greek language. Among these are the independent Church of Greece, the Apostolic Churches of Asia Minor, and those Uniats in the northern part of the Balkan Peninsula who returned to their former allegiance to the Patriarch of Constantinople. In this group we may also include the independent Church of Servia.

II. The Heretical Churches are self-supporting Churches in the countries in which they are situated. They are termed heretical on account of their revolt from the jurisdiction of Constantinople. They hold with the rest of the Church to the doctrine of the Nicene creed as drawn up at the first two Councils, but reject the decisions of the subsequent Councils. They are the Churches in Egypt, Syria, and Armenia, and in those countries known as Kurdistan.

The causes which gave rise to those so-called Heretical Churches are not a little interesting, but cannot be gone into here at any length. They may, however, be referred to as shewing the relation of the Churches of the East to the various Councils.

The Heretical Churches of the East owe

their existence to the actions of the General

Councils subsequent to the Councils of

Nicea and Constantinople. At these the

doctrines accepted by Orthodox and Heretical

Churches alike were distinctly expressed.

But when to the decisions of those

Councils there came to be added the decrees

The Nestorians in like manner accept the

decrees of the first two Councils, and refuse

to entertain the additions made by the

latter Councils, characterising them as unwarranted

alterations of, or additions to

the findings of the first two Councils. The

The third General Council, that of Ephesus, decreed that the title Theotokos (God-bearer) should be applied to the Virgin, and at the Council of Chalcedon this was repeated, affirming that Christ was born of the Theotokos, according to the manhood; the same Symbol affirming that two natures are to be acknowledged in Christ, and that they are indivisible and inseparable. Thus it was that the Nestorians repudiated the decrees alike of Ephesus and Chalcedon, by repudiating the term Theotokos and holding the duality of Christ's nature so as to lose sight of the unity of His Person.

There was nothing for it, therefore, but to separate from the Greek Church (orthodox), and in separation from that Church they became most extensive and powerful.

At the Council of Chalcedon, the fourth

General Council, the now widely acknowledged

doctrine in all the Churches of the

West, as also in the Orthodox Greek Church,

was declared, that Christ was to be acknowledged

in two natures. The Monophysites--those

The Armenian Church is in much the same position; but it has been termed even more heretical than the Jacobite, a very erroneous charge against a Church which is really orthodox. The Armenian Church is separated from the Constantinopolitan by the difference which the accidental absence of the Armenian bishop from the Council of Chalcedon made: the decisions of which were never understood, and of course never formally accepted.

III. The Russian Church includes the

peoples of that great Empire. Christianity

was first preached in Russia at the close

of the tenth century, when Prince Vladimir

was baptised, A.D. 992. Originally, and

for many years this Church, subject to the

Under so many jurisdictions, the Eastern Church is dogmatically one. She has no Confession of Faith; no Thirty-nine Articles: the Bible is her standard, and the Creed of Nicea her expression of dogma.

The Athanasian Creed is found in the Service Books of the Church, but it is not an acknowledged Symbol; and there it differs from the text accepted in the West in the clause relating to the Holy Spirit.

III

In common with the Roman Church, the Greek Church has seven Sacraments. These are--the Eucharist, Baptism, the Holy Chrism, Penance, Matrimony, Unction of the Sick, and Ordination.

Holy Communion.--In relation to this Sacrament, as indeed to all the Sacraments of the Eastern Church, it is necessary to say that, doctrine being in an altogether undefined state, an outsider has considerable difficulty in realising, in any degree of certainty, what the attitude of mind generally of the Church is, or more exactly ought to be. One cannot help feeling that without the mental subtleness of the East, and the atmosphere and environment of its worship, it is impossible to understand, so as to express it, how this Sacrament is viewed. Eastern theology has not been systematised, and could not be--such subtleties and nice distinctions abound, as would defy systematising.

And nowhere as in this Sacrament do we

feel this difficulty more. Transubstantiation

as we understand it, and as it is held in the

West, is nowhere a doctrine of belief in the

Eastern Church, although the language of

the service may seem emphatic, and quite

unmistakable. Under the operation of the

Holy Spirit--not as in the West, after the

formula of institution (and this is an important

That is not the view of the Greek Church. The bread and the wine do not change their substance: they are bread and wine, nothing more, to the end, with this difference, it is a subtle one, doubtless, that the Body and Blood of Christ under the operation of the Holy Ghost are there IN that bread and wine. There is, if we might so express it, Insubstantiation. The materials are not changed, but the Body and Blood of Christ are there.

As a rule, persons go to Holy Communion once a year, shortly after confession. The laity communicate in both kinds, and in this particular the Eastern Church differs from the Western, which withholds the cup from the laity. In other particulars the two Churches differ. The wine is mixed twice, not once; the Sacrament is received standing, not kneeling; and the bread is ordinary leavened bread, not unleavened. As noticed in connection with baptism, infants after that Sacrament partake of the cup, and continue to do so till they reach their seventh year. At that age they are expected to go to Confession, and thereafter they communicate in both kinds.

There are three methods of communion practised in the Eastern Church, (1) Giving the bread first, and thereafter the cup, as is the uniform custom in the West. (2) The priest gives the bread, and the deacon gives the wine with a spoon. (3) The bread is broken into crumbs, and put into the wine, and both are given together in a spoon.

Before the people separate, the priest distributes

the Antidoron. The bread of the

Baptism.--The Eastern Church observes infant baptism, but insists on trine immersion--in the name of the Father, and of the Son, and of the Holy Ghost. A priest is the celebrant; but in cases of sudden and serious illness any orthodox person may perform the rite. In the event, however, of the sick person recovering, a priest must fill in and complete the office.

The form of the service is briefly as follows.

The child having been brought to

church, is anointed with oil, which has been

blessed for the purpose by the priest, on the

breast and back, and on the ears, hands, and

feet. Then follows the profession of the

faith in which the child is baptized. The

The Holy Chrism is the Sacrament of Confirmation in the Eastern Church, and it differs considerably from the Western rite. This Sacrament is given immediately after baptism, not as in the West when the child has come to years of discernment, and in nearly every case by the ordinary priest. Oil is again used, the priest anointing the baptised person with it, making the sign of the Cross--on the forehead, eyes, nostrils, mouth, ears, breast, hands, and feet. Thereafter the child partakes of the wine of the Holy Communion.

Penance.--In the Greek Church Confession

has never assumed the objectionable

features which so largely characterise that

Sacrament in the Roman Church. It is, as

far as it can be made such, a means of

grace; and when used in a right and proper

spirit, helpful to a degree. To quote from

a catechism of the Russian Church, "Penance

is a mystery, in which he who confesses

his sins is, on the outward declaration of the

priest, immediately loosed from his sins by

When the priest has offered up prayer supplicating the mercy of God, the penitent confesses his sins, craving pardon from the just and merciful God, and grace to sin no more. The confessor addressing the penitent reminds him that he has come to God with his sins, and does not confess to man but to God. After he has been dealt with in all faithfulness, the priest tells him that he himself is also an unworthy sinner, and has no power to forgive sins, but relying on the Word of Christ, "Whosesoever sins ye remit," says, "God forgive thee in the world that now is, and in that which is to come."

Penance is prescribed only for mortal

sins; for venial sins absolution alone is

Matrimony.--The first duty of the priest towards persons contemplating marriage is to instruct them in the Ten commandments, the Lord's Prayer, and the Creed. Notice of intended marriage is announced in church some weeks prior to the event, and the ceremony is carried out in church before witnesses.

The Office for Matrimony has two parts, one dealing with betrothal, and the other with the marriage. These may be performed at the same time, or separately, as the case may demand.

Taking the betrothal first. After prayer

for blessing upon the persons, the priest

takes two rings, one of gold and one of

silver, and giving the ring of gold to the

man says, "A., the servant of God, is betrothed

to B., the handmaid of God, in the

name of the Father, and of the Son, and of

the Holy Ghost, now and ever and to the

ages of ages, Amen." Afterwards taking

the silver ring, and giving it to the woman,

he says, "B., the handmaid of God," etc.

Second and third marriages, while allowed, are not looked upon with favour, and the Church shows its disapprobation in several ways. They are not crowned, and the words of the service for such marriages have subtle allusions to their unworthiness. The priest prays, "Give unto them the conversion of the publican, the tears of the harlot, and the confession of the thief, that through repentance they may be deemed worthy of Thy Heavenly Kingdom." The priest does not present Himself at the wedding feast, nor are the parties allowed to partake of the Sacraments of the Church for the space of two years. Fourth marriages are unlawful.

Unction of the Sick.--This Sacrament

must not be confounded with the Sacrament

of Extreme Unction of the Roman Church.

It has its authority in the injunction of the

Apostle James--"Is any sick among you?

let him call for the elders of the Church;

and let them pray over him, anointing him

with oil in the name of the Lord." The oil

Ordination.--This Sacrament, giving as

it does a place in the succession with apostolic

authority, is most jealously guarded.

But before speaking of Ordination, it may

be useful in the first place to give some

description of the vestments worn in the

Greek Church, and with which the clergy

are robed according to their rank. The

origin of the vestments in use in the Greek

Church certainly affords much difficulty. It

is more than likely that they present fundamentally

the dress of the early Greek of

comparatively high social standing in apostolic

We can find no trace of vestments of any kind whatsoever in the Apostolic Church. The garments worn by the apostles and their companions in work would be the dress of the ordinary Greek of fairly high social standing. During the first three centuries, in which Christianity suffered so much at the hands of her enemies, we cannot think of much alteration on dress taking place in the case of the ministers of religion--men had something else to think about. But quieter times came, and no doubt the alterations would then be made to which we have referred; and we can fancy that in making those alterations regard would be had to symbolism, and that garments to suggest certain facts and functions would be brought into use. In making those modifications and additions there can be little doubt that the vestments of the Jewish priesthood with their symbolism would be, as far as possible, approximated.

That those vestments in the early centuries

were purely what they now are,

The first vestment, and that which is common to every order, is the Stoicharion, which corresponds to the Alb in use in the West. It is a white tunicle, not now of linen as formerly, but of silk. The Epimanikia, or hand-pieces, were formerly made in the shape of the sleeves of a surplice, but are now considerably contracted. They hang down on each side of the arm, and are drawn close to it by cords which are fastened tightly round the wrist. The significance of the vestment is not apparent. They are said to represent the cords with which Christ was bound before being delivered to Pilate. Formerly, only bishops wore the Epimanikia, but now they are worn by all ranks.

The Orarion, or praying vestment, is

peculiar to the deacon. It is identical with

the Latin Stole, and is thrown over the left

shoulder. Its significance is obscure, but it

has been represented as symbolising wings,

The Phaenolion.--This word is translated

cloke in I. Tim., iv. 13, and as a vestment

represents the garment which Paul left

at Troas with Carpus. It is the Latin

Chasuble, but is now much reduced in

dimensions. Those five vestments constitute

the dress of a priest. The bishop, in

addition to the five just mentioned, with the

exception of the Phaenolion, for which is

substituted the Saccos which represents the

robe in which Christ was mocked, has two

The office of Ordination is exceedingly

simple and most expressive, and varies

according to the rank of the candidate.

The minor orders are those of Reader,

Singer, Sub-Deacon, and Deacon. If the

candidate be a Reader, he is brought to the

bishop, who counsels him regarding his

duties, and laying his hand upon his head

prays over him, ordaining him to his order.

He is then robed in the Stoicharion and a

copy of the Epistles is put into his hand.

If a Singer, he is robed in like manner, and

The higher orders begin with the priest. In his case the Orarion is exchanged for the Epitrachelion, and the service is arranged to suit the peculiar functions of his order. The additional higher orders are--Proto-presbyter, Abbot, Archimandrite, Bishop, and Metropolitan or Patriarch. It should be stated that the lower grades are necessary steps to the higher ones, and are, as a rule, permanent.

Unlike the Roman Church, which demands

the celibacy of the clergy, the Eastern

One other rank should be mentioned--that of Deaconess or Abbess. It ranks above that of Deacon, and was instituted in order to bring conventual establishments, over which they are set, directly under Episcopal jurisdiction.

The minor rites, canons, and offices, and special prayers of the Eastern Church, are too numerous to be dealt with here. Suffice it to say, that there is no event of ecclesiastical importance which has not its appropriate rite, and scarcely an experience of life for which some provision has not been made in the magnificent services of the Church.

One office of universal interest, however,

we must refer to shortly, viz., that for Burial.

There are five Burial offices in the Euchologion--for

a monk, for a priest, for a child,

The office begins with the following

instruction:--"On the death of one of the

orthodox, straightway the relatives send for

the priest, who, when he is come to the

house in which the remains lie, assumes the

Epitrachelion, and burning incense gives the

blessing, and the relatives, as is usual, say

the Trisagion, the Most Holy Trinity, and

the Lord's Prayer." After certain troparia

are sung, and prayer offered, the remains

are carried to the church and placed in the

narthex (page 52). The service, which is

long and varied, and most impressive, is

made up of scriptural lessons--Psalm i.;

The Beatitudes;

It is deserving of note that the Eastern

Church has a special office for the burial

of little children--an appreciation of the

honour conferred upon them by Christ in

His kingdom, and an acknowledgment of

IV

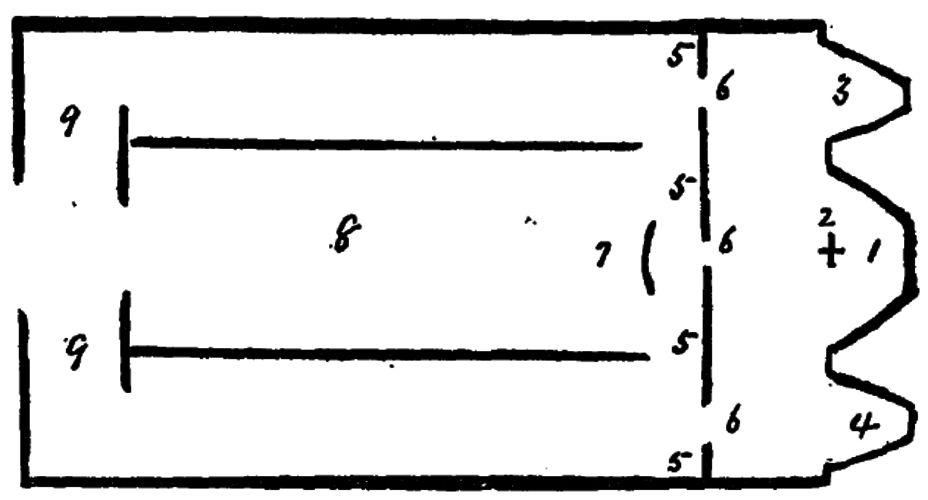

The following is a typical plan, roughly drawn, of a Greek church.

1. The Bema; 2. The Altar; 3. The Prothesis; 4. The Diaconicon; 5. The Iconostasis; 6. Doors; 7. The Ambon; 8. The Nave; 9. The Narthex.

From this plan it will be seen at a glance

that a Greek Church consists of four

parts: (1) The Bema or Sanctuary, which

To look at the arrangement and detail of the church more particularly--

The (ἅγιον βῆμα) Bema or Sanctuary, for the due celebration of the Holy Mysteries, occupies the eastern end of the church. Only priests are allowed to enter the Bema, and by them it can be entered only after fasting and prayer. The altar which stands in the Bema is built of stone, Christ being the Head of the Corner, and the Foundation Stone, and is furnished with candles, a copy of the Scriptures, and the Cross.

The Prothesis, to the north of the Bema,

is a small chapel, on the table of which the

The Diaconicon is to the south of the Bema, and contains the sacred utensils and vestments. It is of inferior sanctity, but the clergy of the lower orders are not allowed to enter it.

The Iconostasis is the screen which separates the sanctuary from the choir, and is so called for the reason that certain icons or pictures are depicted on it. It is of panelled wood, sufficiently high to hide the interior of the sanctuary from the worshippers. In some cases it is simply a curtain of some cloth fabric. It has three doors leading to the Prothesis, to the Bema, and to the Diaconicon. On either side of the door giving entrance to the Bema are the icons of our Lord and of the Virgin Mother--the one to the right and the other to the left. Other icons are displayed over the screen, which in many cases is quite a work of art.

In front of the Iconostasis is the choir,

and opposite the Holy door leading to the

The Nave is that part of the church designed for the accommodation of the male portion of the congregation.

The Narthex gives accommodation to catechumens and penitents, where the Gospels can be heard, but from which the celebration of the Mysteries cannot be witnessed. Late comers usually content themselves with a place in the Narthex in order not to disturb the service. The Narthex is in some cases vaulted, as are also the aisles, so called, over which are galleries for the accommodation of the female portion of the congregation; where these are awanting, women are accommodated in the Narthex, as the division of the sexes during worship is rigidly maintained.

There are no seats in a Greek Church,

as the recognised posture during worship is

standing. In some churches narrow stalls

are built in which the worshipper can stand,

leaning forward, and resting his elbows

during the long service; and in a church

V

The services of the Church are contained in seventeen quarto volumes of closely printed matter. Of these, from a Western point of view, the most important would seem to be:

The Euchologion, which contains the offices of S. Chrysostom and S. Basil, and those for Baptism, Burial, etc.

The Triodion and Pentecostarion contain the services for Lent and the three Sundays preceding it, and for Pentecost. Those two volumes contain the most attractive of all the services of the Church, and their hymnody, which includes much of the work of S. John of Damascus, is incomparable in the whole range of the service books.

The Horologion contains the offices for the eight canonical hours.

The Parakletike or Greater Octoechus, containing the ferial office, is also very rich in hymnody.

The Menaea, of which there are twelve volumes, one for each month of the year, contain the services for saints' days. Service books so many and so voluminous, obviously cannot be in the hands of the people, but it is remarkable to what extent their bulk and intricacies are mastered.

VI

The veneration of saints and relics took its

rise on the overthrow of paganism at the

time of Constantine. It was very natural

that those who had suffered martyrdom at

the hands of pagan persecutors should at

that time be remembered; and so it came to

pass that churches were considered honoured

above all others which contained the relics

of those martyrs. The bones of Christ's

witnesses were removed from their lonely

The chief of saints is the Mother of our Lord after the flesh. The title applied to her--Mother of God--is quite intelligible, when we recollect the strife of the Arian controversy, and the

My Starred Hymns

My Starred Hymns