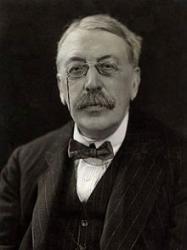

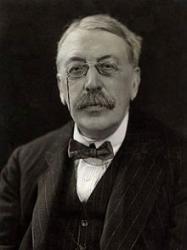

1852 - 1924 Person Name: Charles Villers Stanford Topics: The Sacraments and Rites of the Church Baptism, Confirmation, Reaffirmation Composer of "ENGELBERG" in The United Methodist Hymnal Sir Charles Villiers Stanford (30 September 1852 – 29 March 1924) was an Irish composer, teacher and conductor. Born to a well-off and highly musical family in Dublin, Stanford was educated at the University of Cambridge before studying music in Leipzig and Berlin. He was instrumental in raising the status of the Cambridge University Musical Society, attracting international stars to perform with it.

While still an undergraduate, Stanford was appointed organist of Trinity College, Cambridge. In 1882, aged 29, he was one of the founding professors of the Royal College of Music, where he taught composition for the rest of his life. From 1887 he was also the professor of music at Cambridge. As a teacher, Stanford was sceptical about modernism, and based his instruction chiefly on classical principles as exemplified in the music of Brahms. Among his pupils were rising composers whose fame went on to surpass his own, such as Gustav Holst and Ralph Vaughan Williams. As a conductor, Stanford held posts with the Bach Choir and the Leeds triennial music festival.

Stanford composed a substantial number of concert works, including seven symphonies, but his best-remembered pieces are his choral works for church performance, chiefly composed in the Anglican tradition. He was a dedicated composer of opera, but none of his nine completed operas has endured in the general repertory. Some critics regarded Stanford, together with Hubert Parry and Alexander Mackenzie, as responsible for a renaissance in English music. However, after his conspicuous success as a composer in the last two decades of the 19th century, his music was eclipsed in the 20th century by that of Edward Elgar as well as former pupils.

Stanford was born in Dublin, the only son of John James Stanford and his second wife, Mary, née Henn. John Stanford was a prominent Dublin lawyer, Examiner to the Court of Chancery in Ireland and Clerk of the Crown for County Meath. His wife was the third daughter of William Henn, Master of the High Court of Chancery in Ireland. Both parents were accomplished amateur musicians; John Stanford was a cellist and a noted bass singer who was chosen to perform the title role in Mendelssohn's Elijah at the Irish premiere in 1847. Mary Stanford was an amateur pianist, capable of playing the solo parts in concertos at Dublin concerts.

The young Stanford was given a conventional education at a private day school in Dublin run by Henry Tilney Bassett, who concentrated on the classics to the exclusion of other subjects. Stanford's parents encouraged the boy's precocious musical talent, employing a succession of teachers in violin, piano, organ and composition. Three of his teachers were former pupils of Ignaz Moscheles, including his godmother Elizabeth Meeke, of whom Stanford recalled, "She taught me, before I was twelve years old, to read at sight. … She made me play every day at the end of my lesson a Mazurka of Chopin: never letting me stop for a mistake. … By the time I had played through the whole fifty-two Mazurkas, I could read most music of the calibre my fingers could tackle with comparative ease." One of the young Stanford's earliest compositions, a march in D♭ major, written when he was eight years old, was performed in the pantomime at the Theatre Royal, Dublin three years later. At the age of nine, Stanford gave a piano recital for an invited audience, playing works by Beethoven, Handel, Mendelssohn, Moscheles, Mozart and Bach. One of his songs was taken up by the University of Dublin Choral Society and was well received.

In the 1860s Dublin received occasional visits from international stars, and Stanford was able to hear famous performers such as Joseph Joachim, Henri Vieuxtemps and Adelina Patti. The annual visit of the Italian Opera Company from London, led by Giulia Grisi, Giovanni Matteo Mario and later Thérèse Tietjens, gave Stanford a taste for opera that remained with him all his life. When he was ten, his parents took him to London for the summer, where he stayed with his mother's uncle in Mayfair. While there he took composition lessons from the composer and teacher Arthur O'Leary, and piano lessons from Ernst Pauer, professor of piano at the Royal Academy of Music (RAM). On his return to Dublin, his godmother having left Ireland, he took lessons from Henrietta Flynn, another former Leipzig Conservatory pupil of Moscheles, and later from Robert Stewart, organist of St Patrick's Cathedral, as well as from a third Moscheles pupil, Michael Quarry. During his second spell in London two years later, he met the composer Arthur Sullivan and the musical administrator and writer George Grove, who later played important parts in his career.

John Stanford hoped that his son would follow him into the legal profession but accepted his decision to pursue music as a career. However, he stipulated that Stanford should have a conventional university education before going on to musical studies abroad. Stanford tried unsuccessfully for a classics scholarship at Trinity Hall, Cambridge, but gained an organ scholarship, and later a classics scholarship, at Queens' College. By the time he went up to Cambridge he had written a substantial number of compositions, including vocal music, both sacred and secular, and orchestral works (a rondo for cello and orchestra and a concert overture).

Stanford immersed himself in the musical life of the university to the detriment of his Latin and Greek studies. He composed religious and secular vocal works, a piano concerto, and incidental music for Longfellow's play A Spanish Student. In November 1870 he appeared as piano soloist with the Cambridge University Musical Society (CUMS), and quickly became its assistant conductor and a committee member. The society had declined in excellence since its foundation in 1843. Its choir consisted solely of men and boys; the lack of women singers severely limited the works that the society could present. Stanford was unable to persuade the members to admit women, and so he staged what The Musical Times called "a bloodless revolution." In February 1872 he co-founded a mixed choir, the Amateur Vocal Guild, whose performances immediately put those of the CUMS singers in the shade. The members of CUMS rapidly changed their minds, and agreed to a merger of the two choirs, with women given associate membership of the society.

The conductor of the combined choir was John Larkin Hopkins, who was also organist of Trinity College. He became ill, and handed over the conductorship to Stanford in 1873. Stanford was also appointed Hopkins's deputy organist at Trinity, and moved from Queens' to Trinity in April 1873. In the summer of that year Stanford made his first trip to continental Europe. He went to Bonn for the Schumann Festival held there, where he met Joachim and Brahms. His growing love of the music of Schumann and Brahms marked him as a classicist at a time when many music-lovers were divided into the classical or the modernist camps, the latter represented by the music of Liszt and Wagner. Stanford was not constrained by the fashion for belonging to one camp or the other; he immensely admired Die Meistersinger though he was unenthusiastic about some of Wagner's other works. After leaving Bonn he returned home by way of Switzerland and then Paris, where he saw Meyerbeer's Le prophète.

Hopkins's illness proved fatal, and after his death the Trinity authorities invited Stanford to take over as organist of the college. He accepted with the proviso that he was to be released each year for a spell of musical study in Germany. The fellows of the college resolved on 21 February 1874:

Two days after his appointment, Stanford took the final examinations for his classics degree. He ranked 65th of 66, and was awarded a third-class degree.

On the recommendation of Sir William Sterndale Bennett, former professor of music at Cambridge and now director of the Royal Academy of Music, Stanford went to Leipzig in the summer of 1874 for lessons with Carl Reinecke, professor of composition and piano at the Leipzig Conservatory. The composer Thomas Dunhill commented that by 1874 it was "the tail-end of the Leipzig ascendancy, when the great traditions of Mendelssohn had already begun to fade." Nevertheless, Stanford did not seriously consider studying anywhere else. Neither Dublin nor London offered any comparable musical training; the most prestigious British music school, the RAM, was at that time hidebound and reactionary. He was dismayed to find in Leipzig that Bennett had recommended him to a German pedant no more progressive than the teachers at the RAM. Stanford said of Reinecke, "Of all the dry musicians I have ever known he was the most desiccated. He had not a good word for any contemporary composer… He loathed Wagner … sneered at Brahms and had no enthusiasm of any sort." Stanford's biographer Paul Rodmell suggests that Reinecke's ultra-conservatism may have been unexpectedly good for his pupil "as it may have encouraged Stanford to kick against the traces." During his time in Leipzig Stanford took piano lessons from Robert Papperitz (1826–1903), organist of the city's Nikolaikirche, whom he found more helpful.

Among Stanford's compositions in 1874 was a setting of part one of Longfellow's poem "The Golden Legend." He intended to set the entire poem, but gave up, defeated by Longfellow's "numerous but unconnected characters." Stanford ignored this and other early works when assigning opus numbers in his mature years. The earliest compositions in his official list of works are a four-movement Suite for piano and a Toccata for piano, which both date from 1875.

After a second spell in Leipzig with Reinecke in 1875, which was no more productive than the first, Stanford was recommended by Joachim to study in Berlin the following year with Friedrich Kiel, whom Stanford found "a master at once sympathetic and able … I learnt more from him in three months, than from all the others in three years."

Returning to Cambridge in the intervals of his studies in Germany, Stanford had resumed his work as conductor of CUMS. He found the society in good shape under his deputy, Eaton Faning, and able to tackle demanding new works. In 1876 the society presented one of the first performances in Britain of the Brahms Requiem. In 1877 CUMS came to national attention when it presented the first British performance of Brahms's First Symphony.

During the same period, Stanford was becoming known as a composer. He was composing prolifically, though he later withdrew some of his works from these years, including a violin concerto which, according to Rodmell, suffered from "undistinguished thematic material." In 1875 his First Symphony won the second prize in a competition held at the Alexandra Palace for symphonies by British composers, although he had to wait a further two years to hear the work performed. In the same year Stanford directed the first performance of his oratorio "The Resurrection," given by CUMS. At the request of Alfred Tennyson, he wrote incidental music for Tennyson's drama Queen Mary, performed at the Lyceum Theatre, London in April 1876.

In April 1878, despite the disapproval of his father, Stanford married Jane Anna Maria Wetton, known as Jennie, a singer whom he had met when she was studying in Leipzig. They had a daughter, Geraldine Mary, born in 1883 and a son, Guy Desmond, born in 1885.

In 1878 and 1879 Stanford worked on his first opera, The Veiled Prophet, to a libretto by his friend William Barclay Squire. It was based on a poem by Thomas Moore with characters including a virgin priestess and a mystic prophet, and a plot that culminates in poisoning and stabbing. Stanford offered the work to the opera impresario Carl Rosa, who refused it and suggested that the composer should try to have it staged in Germany: "Its success will (unfortunately) have much greater chances here if accepted abroad." Referring to the enormous popularity of Sullivan's comic operas, Rosa added, "If the work was of the Pinafore style it would be quite another matter." Stanford had greatly enjoyed Sullivan's Cox and Box, but The Veiled Prophet was intended to be a serious work of high drama and romance. Stanford had made many useful contacts during his months in Germany, and his friend the conductor Ernst Frank got the piece staged at the Königliches Schauspiel in Hanover in 1881. Reviewing the premiere for The Musical Times, Stanford's friend J A Fuller Maitland wrote, "Mr. Stanford's style of instrumentation … is built more or less on that of Schumann; while his style of dramatic treatment bears more resemblance to Meyerbeer than to that of any other master." Other reviews were mixed, and the opera had to wait until 1893 for its English premiere. Stanford nevertheless continued to seek operatic success throughout his career. In his lifelong enthusiasm for opera he differed strikingly from his contemporary Hubert Parry, who made one attempt at composing opera and then renounced the genre.

By the early 1880s, Stanford was becoming a major figure in the British musical scene. His only major rivals were seen as Sullivan, Frederic Hymen Cowen, Parry, Alexander Mackenzie and Arthur Goring Thomas. Sullivan was by this time viewed with suspicion in high-minded musical circles for composing comic rather than grand operas; Cowen was regarded more as a conductor than as a composer; and the other three, though seen as promising, had not so far made a clear mark as Stanford had done. Stanford helped Parry in particular to gain recognition, commissioning incidental music from him for a Cambridge production of Aristophanes' The Birds and a symphony (the "Cambridge") for the musical society. At Cambridge Stanford continued to raise the profile of CUMS, as well as his own, by securing appearances by leading international musicians including Joachim, Hans Richter, Alfredo Piatti and Edward Dannreuther. The society attracted further attention by premiering works by Cowen, Parry, Mackenzie, Goring Thomas and others. Stanford was also making an impression in his capacity as organist of Trinity, raising musical standards and composing what his biographer Jeremy Dibble calls "some highly distinctive church music" including a Service in B♭ (1879), the anthem "The Lord is my shepherd" (1886) and the motet Justorum animae (1888).

In the first half of the 1880s, Stanford collaborated with the author Gilbert à Beckett on two operas, Savonarola, and The Canterbury Pilgrims. The former was well received at its premiere in Hamburg in April 1884, but received a critical savaging when staged at Covent Garden in July of the same year. Parry commented privately, "It seems very badly constructed for the stage, poorly conceived and the music, though clean and well-managed, is not striking or dramatic." The most severe public criticism was in The Theatre, whose reviewer wrote, "The book of Savonarola is dull, stilted, and, from a dramatic point of view, weak. It is not, however, so crushingly tiresome as the music fitted to it. Savonarola has gone far to convince me that opera is quite out of [Stanford's] line and that the sooner he abandons the stage for the cathedral, the better for his musical reputation." The Canterbury Pilgrims had been premiered in London in April 1884, three months before Savonarola was presented at Covent Garden. It had a better reception than the latter, though reviews pointed out Stanford's debt to Die Meistersinger, and complained of a lack of emotion in the love music. George Grove agreed with the critics, writing to Parry, "Charlie's music contains everything but sentiment. Love not at all – that I heard not a grain of. … And I do think that there might be more tune. Melody is not a thing to be avoided surely." In 1896 a critic wrote that the opera had "just such a 'book' as would have suited the late Alfred Cellier. He would probably have made of it a charming light English opera. But Dr. Stanford has chosen to use it for the exemplification of those advanced theories which we know him to hold, and he has given us music which would incline us to think that Die Meistersinger had been his model. The effect of the combination is not happy."

In 1883, the Royal College of Music was set up to replace the short-lived and unsuccessful National Training School for Music (NTSM). Neither the NTSM nor the longer-established Royal Academy of Music had provided adequate musical training for professional orchestral players, and the founder-director of the college, George Grove, was determined that the new institution should succeed in doing so. His two principal allies in this undertaking were the violinist Henry Holmes and Stanford. In a study of the founding of the college, David Wright notes that Stanford had two main reasons for supporting Grove's aim. The first was his belief that a capable college orchestra was essential to give students of composition the chance to experience the sound of their music. His second reason was the severe contrast between the competence of German orchestras and the performance of their British counterparts. He accepted Grove's offer of the posts of professor of composition and (with Holmes) conductor of the college orchestra. He held the professorship for the rest of his life; among the best known of his many pupils were Samuel Coleridge-Taylor, Gustav Holst, Ralph Vaughan Williams, John Ireland, Frank Bridge and Arthur Bliss.

Stanford was never an easy-going teacher. He insisted on one-to-one tutorials, and worked his pupils hard. One of them, Herbert Howells, recalled, "Corner any Stanford pupil you like, and ask him to confess the sins he most hated being discovered in by his master. He will tell you 'slovenliness' and 'vulgarity.' When these went into the teacher's room they came out, badly damaged. Against compromise with dubious material or workmanship Stanford stubbornly set his face." Another pupil, Edgar Bainton, recalled:

Stanford's teaching seemed to be without method or plan. His criticism consisted for the most part of "I like it, my boy," or "It's damned ugly, my boy" (the latter in most cases). In this, perhaps, lay its value. For in spite of his conservatism, and he was intensely and passionately conservative in music as in politics, his amazingly comprehensive knowledge of musical literature of all nations and ages made one feel that his opinions, however irritating, had weight.

To Stanford's regret, many of his pupils who achieved eminence as composers broke away from his classical, Brahmsian precepts, as he had himself rebelled against Reinecke's conservatism. The composer George Dyson wrote, "In a certain sense the very rebellion he fought was the most obvious fruit of his methods. And in view of what some of these rebels have since achieved, one is tempted to wonder whether there is really anything better a teacher can do for his pupils than drive them into various forms of revolution." The works of some of Stanford's pupils, including Holst and Vaughan Williams, entered the general repertory in Britain, and to some extent elsewhere, as Stanford's never did. For many years after his death it seemed that Stanford's greatest fame would be as a teacher. Among his achievements at the RCM was the establishment of an opera class, with at least one operatic production every year. From 1885 to 1915 there were 32 productions, all of them conducted by Stanford.

In 1887 Stanford was appointed professor of music at Cambridge in succession to Sir George Macfarren who died in October of that year. Up to this time, the university had awarded music degrees to candidates who had not been undergraduates at Cambridge; all that was required was to pass the university's music examinations. Stanford was determined to end the practice, and after six years he persuaded the university authorities to agree. Three years' study at the university became a prerequisite for sitting the bachelor of music examinations.

During the last decades of the 19th century, Stanford's academic duties did not prevent him from composing or performing. He was appointed conductor of the Bach Choir, London, in 1885, succeeding its founding conductor Otto Goldschmidt. He held the post until 1902. Hans von Bülow conducted the German premiere of Stanford's Irish Symphony in Hamburg in January 1888, and was sufficiently impressed by the work to programme it in Berlin shortly afterwards. Richter conducted it in Vienna, and Mahler later conducted it in New York. For the Theatre Royal, Cambridge, Stanford composed incidental music for productions of Aeschylus's The Eumenides (1885), and Sophocles' Oedipus Tyrannos (1887). The Times said of the former, "Mr. Stanford's music is dramatically significant, as well as beautiful in itself. It has, moreover, that quality so rare among modern composers – style." In both sets of music Stanford made extensive use of leitmotifs, in the manner of Wagner; the critic of The Times noted the Wagnerian character of the prelude to Oedipus.

In the 1890s, Bernard Shaw writing as "Corno di Bassetto", music critic of The World, voiced mixed feelings about Stanford. In Shaw's view, the best of Stanford's works displayed an uninhibited, Irish, character. The critic was dismissive of the composer's solemn Victorian choral music. In July 1891, Shaw's column was full of praise for Stanford's capacity for spirited tunes, declaring that Richard D'Oyly Carte should engage him to succeed Sullivan as the composer of Savoy operas. In October of the same year, Shaw attacked Stanford's oratorio Eden, bracketing the composer with Parry and Mackenzie as a mutual admiration society, purveying "sham classics":

[W]ho am I that I should be believed, to the disparagement of eminent musicians? If you doubt that Eden is a masterpiece, ask Dr Parry and Dr Mackenzie, and they will applaud it to the skies. Surely Dr Mackenzie’s opinion is conclusive; for is he not the composer of Veni Creator, guaranteed as excellent music by Professor Stanford and Dr Parry? You want to know who Parry is? Why, the composer of "Blest Pair of Sirens," as to the merits of which you only have to consult Dr Mackenzie and Professor Stanford.

To Fuller Maitland, the trio of composers lampooned by Shaw were the leaders of an English musical renaissance (although neither Stanford nor Mackenzie was English). This view persisted in some academic circles for many years.

Stanford returned to opera in 1893, with an extensively revised and shortened version of The Veiled Prophet. It had its British premiere at Covent Garden in July. His friend Fuller Maitland was by this time the chief music critic of The Times, and the paper's review of the opera was laudatory. According to Fuller Maitland The Veiled Prophet was the best novelty of an opera season that had also included Leoncavallo's Pagliacci, Bizet's Djamileh and Mascagni's I Rantzau. Stanford's next opera was Shamus O'Brien (1896), a comic opera to a libretto by George H. Jessop. The conductor was the young Henry Wood, who recalled in his memoirs that the producer, Sir Augustus Harris, managed to quell the dictatorial composer and prevent him from interfering with the staging. Stanford attempted to give Wood lessons in conducting, but the young man was unimpressed. The opera was successful, running for 82 consecutive performances. The work was given in German translation in Breslau in 1907; Thomas Beecham thought it "a colourful, racy work", and revived it in his 1910 opéra comique season at His Majesty's Theatre, London.

At the end of 1894, Grove retired from the Royal College of Music. Parry was chosen to succeed him, and although Stanford wholeheartedly congratulated his friend on his appointment, their relations soon deteriorated. Stanford was known as a hot-tempered and quarrelsome man. Grove had written of a board meeting at the Royal College "where somehow the spirit of the d----l himself had been working in Stanford all the time – as it sometimes does, making him so nasty and quarrelsome and contradictious as no one but he can be! He is a most remarkably clever and able fellow, full of resource and power – no doubt of that – but one has to purchase it often at a very dear price." Parry suffered worse at Stanford's hands with frequent rows, deeply upsetting to the highly-strung Parry. Some of their rows were caused by Stanford's reluctance to accept the authority of his old friend and protégé, but on other occasions Parry seriously provoked Stanford, notably in 1895 when he reduced the funding for Stanford's orchestral classes.

In 1898, Sullivan, ageing and unwell, resigned as conductor of the Leeds triennial music festival, a post which he had held since 1880. He believed that Stanford's motive for accepting the conductorship of the Leeds Philharmonic Society the previous year was to position himself to take over the festival. Stanford later felt obliged to write to The Times, denying that he had been party to a conspiracy to oust Sullivan. Sullivan was by then thought to be a dull conductor of other composers' music, and although Stanford's work as a conductor was not without its critics, he was appointed in Sullivan's place. He remained in charge until 1910. His compositions for the festival included "Songs of the Sea" (1904), "Stabat Mater" (1907) and "Songs of the Fleet (1910)." New works by other composers presented at Leeds during Stanford's years in charge included pieces by Parry, Mackenzie, and seven of Stanford's former pupils. The best-known new work from Stanford's time is probably Vaughan Williams's A Sea Symphony, premiered in 1910.

In 1901 Stanford returned once again to opera, with a version of Much Ado About Nothing, to a libretto by Julian Sturgis that was exceptionally faithful to Shakespeare's original. The Manchester Guardian commented, "Not even in the Falstaff of Arrigo Boito and Giuseppe Verdi have the characteristic charm, the ripe and pungent individuality of the original comedy been more sedulously preserved."

Despite good notices for the opera, Stanford's star was waning. In the first decade of the century, his music became eclipsed by that of a younger composer, Edward Elgar. In the words of the music scholar Robert Anderson, Stanford "had his innings with continental reputation in the latter decades of the nineteenth century, but then Elgar bowled him out." When Elgar was struggling for recognition in the 1890s, Stanford had been supportive of his younger colleague, conducting his music, putting him forward for a Cambridge doctorate, and proposing him for membership of the exclusive London club, the Athenaeum. He was, however, put out when Elgar's success at home and abroad eclipsed his own, with Richard Strauss (whom Stanford detested) praising Elgar as the first progressive English composer. When Elgar was appointed professor of music at Birmingham University in 1904, Stanford wrote him a letter that the recipient found "odious". Elgar retaliated in his inaugural lecture with remarks about composers of rhapsodies, widely seen as denigrating Stanford. Stanford later counter-attacked in his book A History of Music, writing of Elgar, "Cut off from his contemporaries by his religion and his want of regular academic training, he was lucky enough to enter the field and find the preliminary ploughing done."

Though bitter about being sidelined, Stanford continued to compose. Between the turn of the century and the outbreak of the First World War in 1914 his new works included a violin concerto (1901), a clarinet concerto (1902), a sixth and a seventh (and last) symphony (1906 and 1911), and his second piano concerto (1911). In 1916 he wrote his penultimate opera, The Critic. It was a setting of Sheridan's comedy of the same name, with the original text left mostly intact by the librettist, Lewis Cairns James. The work was well received at the premiere at the Shaftesbury Theatre, London, and was taken up later in the year by Beecham, who staged it in Manchester and London.

The First World War had a severe effect on Stanford. He was frightened by air-raids, and had to move from London to Windsor to avoid them. Many of his former pupils were casualties of the fighting, including Arthur Bliss, injured, Ivor Gurney, gassed, and George Butterworth, killed. The annual RCM operatic production, which Stanford had supervised and conducted every year since 1885, had to be cancelled. His income declined, as the fall in student numbers at the college reduced the demand for his services. After a serious disagreement at the end of 1916, his relationship with Parry deteriorated to the point of hostility. Stanford's magnanimity, however, came to the fore when Parry died two years later and Stanford successfully lobbied for him to be buried in St Paul's Cathedral.

After the war, Stanford handed over much of the direction of the RCM's orchestra to Adrian Boult, but continued to teach at the college. He gave occasional public lectures, including one on "Some Recent Tendencies in Composition", in January 1921 which was belligerently hostile to most of the music of the generation after his own. His last public appearance was on 5 March 1921 conducting the Royal Choral Society in his new cantata, At the Abbey Gate. Reviews were polite but unenthusiastic. The Times said, "we could not feel that the music had enough emotion behind it", The Observer thought it "quite appealing even though one feels it to be more facile than powerful."

In September 1922, Stanford completed the sixth Irish Rhapsody, his final work. Two weeks later he celebrated his 70th birthday; thereafter his health declined. On 17 March 1924 he suffered a stroke and on 29 March he died at his home in London, survived by his wife and children. He was cremated at Golders Green Crematorium on 2 April and his ashes were buried in Westminster Abbey the following day. The orchestra of the Royal College of Music, conducted by Boult, played music by Stanford, ending the service with a funeral march that he had written for Tennyson's Becket in 1893. The grave is in the north choir aisle of the Abbey, near the graves of Henry Purcell, John Blow and William Sterndale Bennett. The Times said, "the conjunction of the music of Stanford with that of his great predecessors showed how thoroughly as composer he belonged to their line."

Stanford's last opera, The Travelling Companion, composed during the war, was premiered by amateur performers at the David Lewis Theatre, Liverpool in 1925 with a reduced orchestra. The work was given complete at Bristol in 1928 and at Sadler's Wells Theatre, London, in 1935.

Stanford received many honours, including honorary doctorates from Oxford (1883), Cambridge (1888), Durham (1894), Leeds (1904), and Trinity College, Dublin (1921). He was knighted in 1902 and in 1904 was elected a member of the Royal Academy of Arts, Berlin.

In Stanford's music the sense of style, the sense of beauty, the feeling of a great tradition is never absent. His music is in the best sense of the word Victorian, that is to say it is the musical counterpart of the art of Tennyson, Watts and Matthew Arnold.

Stanford composed about 200 works, including seven symphonies, about 40 choral works, nine operas, 11 concertos and 28 chamber works, as well as songs, piano pieces, incidental music, and organ works. He suppressed most of his earliest compositions; the earliest of works that he chose to include in his catalogue date from 1875.

Throughout his career as a composer, Stanford's technical mastery was rarely in doubt. The composer Edgar Bainton said of him, "Whatever opinions may be held upon Stanford's music, and they are many and various, it is, I think, always recognised that he was a master of means. Everything he turned his hand to always 'comes off.'" On the day of Stanford's death, one former pupil, Gustav Holst, said to another, Herbert Howells, "The one man who could get any one of us out of a technical mess is now gone from us."

After Stanford's death most of his music was quickly forgotten, with the exception of his works for church performance. His Stabat Mater and Requiem held their place in the choral repertoire, the latter championed by Sir Thomas Beecham. Stanford's two sets of sea songs and the song "The Blue Bird" were still performed from time to time, but even his most popular opera, Shamus O'Brien came to seem old fashioned with its "stage-Irish" vocabulary. However, in his 2002 study of Stanford Dibble writes that the music, increasingly available on disc if not in live performance, still has the power to surprise. In Dibble's view, the frequent charge that Stanford is "Brahms and water" was disproved once the symphonies and concertos, much of the chamber music and many of the songs became available for reappraisal when recorded for compact disc. In 2002, Rodmell's study of Stanford included a discography running to 16 pages.

The criticism most often made of Stanford's music by writers from Shaw onwards is that his music lacks passion. Shaw praised "Stanford the Celt" and abominated "Stanford the Professor", who reined in the emotions of the Celt. In Stanford's church music, the critic Nicholas Temperley finds "a thoroughly satisfying artistic experience, but one that is perhaps lacking in deeply felt religious impulse." In his operas and elsewhere, Grove, Parry and later commentators found music that ought to convey love and romance failing to do so. Like Parry, Stanford strove for seriousness, and his competitive streak led him to emulate Sullivan not in comic opera, for which Stanford had a real gift, but in oratorio in what Rodmell calls grand statements that "only occasionally matched worthiness with power or profundity."

--excerpts from en.wikipedia.org

Charles V. Stanford