- |

User Links

Praise for the Fountain opened

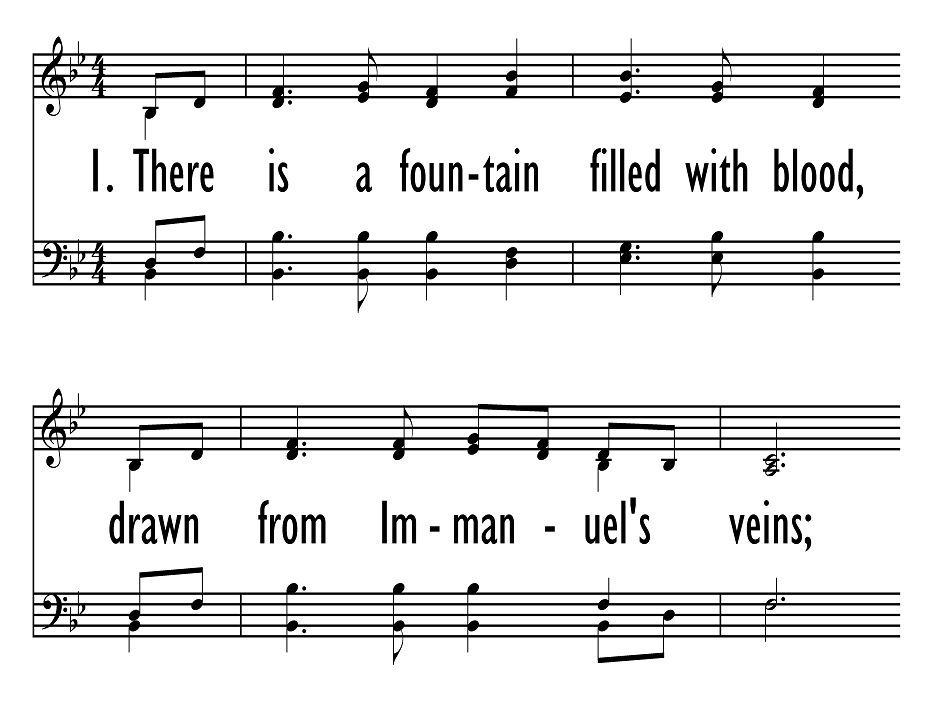

There is a fountain filled with blood Drawn from Emmanuel's veins

Author: William Cowper (1772)Tune: CLEANSING FOUNTAIN (13565)

Communion Songs

Published in 2520 hymnals

Printable scores: PDF, MusicXMLPlayable presentation: Lyrics only, lyrics + musicAudio files: MIDI, Recording

Representative Text

1 There is a fountain filled with blood

Drawn from Immanuel's veins;

And sinners, plunged beneath that flood,

Lose all their guilty stains:

Lose all their guilty stains,

Lose all their guilty stains;

And sinners, plunged beneath that flood,

Lose all their guilty stains.

2 The dying thief rejoiced to see

That fountain in his day;

And there may I, though vile as he,

Wash all my sins away:

Wash all my sins away,

Wash all my sins away;

And there may I, though vile as he,

Wash all my sins away.

3 Dear dying Lamb, Thy precious blood

Shall never lose its pow'r,

Till all the ransomed Church of God

Be saved, to sin no more:

Be saved, to sin no more,

Be saved, to sin no more;

Till all the ransomed Church of God

Be saved to sin no more.

4 E'er since by faith I saw the stream

Thy flowing wounds supply,

Redeeming love has been my theme,

And shall be till I die:

And shall be till I die,

And shall be till I die;

Redeeming love has been my theme,

And shall be till I die.

5 When this poor lisping, stamm'ring tongue

Lies silent in the grave,

Then in a nobler, sweeter song

I'll sing Thy pow'r to save:

I'll sing Thy pow'r to save,

I'll sing Thy pow'r to save;

Then in a nobler, sweeter song

I'll sing Thy pow'r to save.

Sing Joyfully, 1989

Author: William Cowper

William Cowper (pronounced "Cooper"; b. Berkampstead, Hertfordshire, England, 1731; d. East Dereham, Norfolk, England, 1800) is regarded as one of the best early Romantic poets. To biographers he is also known as "mad Cowper." His literary talents produced some of the finest English hymn texts, but his chronic depression accounts for the somber tone of many of those texts. Educated to become an attorney, Cowper was called to the bar in 1754 but never practiced law. In 1763 he had the opportunity to become a clerk for the House of Lords, but the dread of the required public examination triggered his tendency to depression, and he attempted suicide. His subsequent hospitalization and friendship with Morley and Mary Unwin provided emotional st… Go to person page >

William Cowper (pronounced "Cooper"; b. Berkampstead, Hertfordshire, England, 1731; d. East Dereham, Norfolk, England, 1800) is regarded as one of the best early Romantic poets. To biographers he is also known as "mad Cowper." His literary talents produced some of the finest English hymn texts, but his chronic depression accounts for the somber tone of many of those texts. Educated to become an attorney, Cowper was called to the bar in 1754 but never practiced law. In 1763 he had the opportunity to become a clerk for the House of Lords, but the dread of the required public examination triggered his tendency to depression, and he attempted suicide. His subsequent hospitalization and friendship with Morley and Mary Unwin provided emotional st… Go to person page >Text Information

Related Texts

| First Line: | There is a fountain filled with blood Drawn from Emmanuel's veins |

| Title: | Praise for the Fountain opened |

| Author: | William Cowper (1772) |

| Meter: | 8.6.8.6 |

| Language: | English |

| Refrain First Line: | Will you wash in the crimson tide |

| Notes: | Polish translation: See "Jest źródło skąd na grzeszny świat" by Paweł Sikora; Swahili translations: See "Ni damu idondokayo", "Kuna chemchem itokayo", "Domu imebubujika, Ni ya Imanueli |

| Copyright: | Public Domain |

| Liturgical Use: | Communion Songs |

- (hymns)

- (hymns)

- (hymns)

- (hymns)

- (hymns)

- (hymns)

- (hymns)

- (hymns)

- Zechariah 15:1 (hymns)

- (hymns)

- (hymns)

- (hymns)

- (hymns)

- (hymns)

- (hymns)

- (hymns)

- (hymns)

- (hymns)

- (hymns)

- (hymns)

- (hymns)

- (hymns)

- (hymns)

- (hymns)

- (hymns)

- (hymns)

- (hymns)

- (hymns)

- (hymns)

- (hymns)

- (hymns)

- (hymns)

- (hymns)

- (hymns)

- (hymns)

- (hymns)

Chinese

Engish

English

- 112 Familiar Hymns and Gospel Songs #96

- 52 Hymns of the Heart: with an appendix of favorite solos and choruses (Missionary and Church Extension Ed.) #53

- A Baptist Hymn Book, Designed Especially for the Regular Baptist Church and All Lovers of Truth #d740

- A Book of Worship for the Use of the Evangelical Lutheran Church ... of the Church of the Redeemer, Richmond, Virginia #d163

- A Choice Collection of Hymns, and Spiritual Songs, designed for the devotions of Israel, in prayer, conference, and camp-meetings...(2nd ed.) #36

- A Choice Collection of Hymns, in which are some never before printed #CXCI

- A choice collection of popular songs with some standard hymns for young people's meetings (Silver and Gold No. 1) #d127

- A Choice Selection of Evangelical Hymns, from various authors: for the use of the English Evangelical Lutheran Church in New York #57

- A Choice Selection of Hymns and Spiritual Songs for the use of the Baptist Church and all lovers of song #192

- A Chord #d107 10 shown out of 1686

Norwegian

Notes

There is a Fountain filled with blood. W. Cowper. [Passiontide.] This hymn was probably written in 1771, as it is in Conyers's Collection of Psalms and Hymns, 1772, in 7 stanzas of 4 lines. It was republished in the Olney Hymns, 1779, Bk. i., No. 79, with the heading "Praise for the Fountain opened." It is based on Zech. xiii. 1, "In that day there shall be a Fountain opened to the house of David and to the inhabitants of Jerusalem for sin and for uncleanness." This hymn in full or abbreviated is in extensive use in all English-speaking countries.

A well known form of this hymn is "From Calvary's Cross a Fountain flows." This appeared in Cotterill's Selection, 8th ed., 1819, No. 43, in 5 stanzas of 4 lines, and consists of stanzas i.-v. very much altered. In Bickersteth's Christian Psalmody, 1833, No. 49, that same opening stanza is given, with a return, in most of the remaining six stanzas, to the original text. The question as to by whom these alterations were made, first in Cotterill's Selection off 1819, and then in Bickersteth's Christian Psalmody, 1833, is answered by R. W. Dibdin, in the Christian Annotator, vol. iii., No. 76, for July 5, 1856, p. 278, where he writes concerning this hymn:—

"About 18 years ago, I was regretting to the late James Montgomery, the poet, of Sheffield, that hymns were so frequently printed differently from the originals as written by their authors. I pointed out the very hymn mentioned in the Rev. Edward Bickersteth's Collection as an example. He smiled, and said,'I altered it as you see it there; Bickersteth asked me to alter it.'"

We know from Montgomery's Memoirs that he altered hymns for Cotterill's 1819 edition of his Selection and here by his own confession we have one of those alterations. Previously to this, however, he had acknowledged having rewritten the 1819 text as in Cotterill's Selection in these words:—

”I entirely rewrote the first verse of that favourite hymn, commencing ‘There is a Fountain filled with blood.' The words are objectionable as representing a fountain being filled, instead of springing up; I think my version is unexceptional."

In these alterations of the text the sustained confidence and rapture of Cowper are entirely lost. This may suit public taste, but it gives an entirely false view of the state of Cowper's mind when he wrote this hymn. Our positive knowledge of the poet's frequent depression of spirits and despair is painful enough without this gratuitous and false addition thereto. Five stanzas of this hymn, taken from the commonly received text, are rendered into Latin in R. Bingham's Hymnologia Christiana Latina, 1871, as: "Fons est sanguine redundans." Dr. H. M. Macgill has however taken the original text for his rendering into Latin in his Songs of the Christian Creed and Life, 1876, where it reads:—"Sanguis en Emmanuelis." In addition to Latin, various forms of the text have been translated into many other languages.

--Excerpts from John Julian, Dictionary of Hymnology (1907)

For Leaders

When William Cowper, who had suffered from severe depression since the death of his mother when he was just six years old, was faced with the prospect of a final law examination before the House of Lords, he experienced a mental breakdown that he never fully recovered from. Having been sent to St. Alban’s asylum for eighteen months, he began to read the Bible, which brought some peace to his mind, and he was able to leave and live with his good family friend, famed author of “Amazing Grace,” John Newton. Newton helped Cowper recover, and together Cowper and Newton wrote poetry and religious verse, which they later published in their own hymnal. “There is a Fountain Filled With Blood” is one such hymn, and it is a dramatic illustration of Cowper’s faith. The last verse in particular speaks to Cowper’s hope of redemption; it reads, “When this poor lisping, stamm’ring tongue lies silent in the grave, then in a nobler, sweeter song I’ll sing thy pow’r to save.” The mental breakdown at his examination gave Cowper a lisp and stutter that he had the rest of his life, but he knew there was a greater song to be sung than any his earthly voice could raise, a song of praise to the dying Lamb.

Text:

Cowper’s original text has undergone a few changes – many of them in the early nineteenth century by the hymn writer James Montgomery. While not all of these changes stuck, this change remains in many hymnals: in the 2nd verse, the last lines were changed from the declarative “and there have I, as vile as he, wash’d all my sins away,” to the prayerful “and there would I though vile as he, wash all my sins away.” I think this is a good change to the original, since it acknowledges that though Christ paid the price, we are still sinners in need of cleansing each and every day, waiting for the day when we will be washed clean forever.

Now, as mentioned in the teaser paragraph, the first line of this text has raised some eyebrows and made some folks uncomfortable. The imagery of a fountain being filled with blood and then standing beneath that fountain as the blood pours over you isn’t the prettiest image. But then, when did we ever say our faith was pretty? Ray Palmer writes that this criticism “takes the words as if they were intended to be a literal prosaic statement. It forgets that what they express is not only poetry, but the poetry of intense and impassioned feeling, which naturally embodies itself in the boldest metaphors. The inner sense of the soul, when its deepest affections are moved, infallibly takes these metaphors in their true significance” (Lutheran Hymnal Handbook). The particularly uncomfortable and gruesome language of the first verse is meant to be just that – an expression of our deep discomfort when we acknowledge the awesome act of salvation made for each one of us. And the hymn doesn’t stop here. As we continue to sing, the gruesome imagery is layered upon by beautiful images of joy, faith, and hope. Isn’t this hymn then a true representation of the Christian walk? Pain and guilt, washed white by God’s grace – something worth singing about.

Tune:

The tune CLEANSING FOUNTAIN was written by Lowell Mason in 1830 for Cowper’s text, and was first published in Thomas Hastings’ Spiritual Songs for Social Worship (1832). When this tune is taken too quickly, as is often done, it’s difficult to really sit with the words and dwell on the meaning of the text. A fast tempo can in fact cheapen the words, causing them to lose their power. Take it slow on this one – don’t drag – but give the congregation enough time to really chew on the words. Also, the moment you sweep up to the last line into the repeats is a big moment, so don’t be afraid to really emphasize the high notes.

Here are some versions and variations for arrangement inspiration:

- Selah has a great example of those big moments and powerful high notes

- Karl Digerness of Cityhymns has a re-tuned version that nicely slows down the tempo and presents the text in a very reflective way.

When/Why/How:

With some imagery of the Passion, this hymn works beautifully for both Lent and Easter, especially during Communion. However, the imagery is also generic enough to be used throughout the year as a communion hymn.

Suggested music:

- Whalum, Wendell. There Is a Fountain - for Choir, used the tune HEBER by George Kingsley

- Joubert, Joseph. The Precious Blood of Jesus - for Choir, a medley of "There Is a Founatain" "The Blood Will Never Lose It's Power" by Andraé Crouch and "Lamb of God" by Twila Paris

- Lamb, Linda. There Is A Fountain - for Handbells

Laura de Jong, Hymnary.org

Timeline

Arrangements

Media

Sing Joyfully #300

The United Methodist Hymnal #622

- MIDI file from Baptist Hymnal 1991 #142

- MIDI file from Baptist Hymnal 1991 #142

- Audio recording from Baptist Hymnal 2008 #224

- MIDI file from Beulah Songs: a choice collection of popular hymns and music, new and old. Especially adapted to camp meetings, prayer and conference meetings, family worship, and all other assemblies... #83

- MIDI file from Crowning Day No. 2 #148

- MIDI file from The Cyber Hymnal #6556

- MIDI file from Hymnal and Liturgies of the Moravian Church #110

- MIDI file from Joyful Sound: a collection of new hymns and music with familiar selections #169

- MIDI file from Make Christ King: a selection of high class gospel music for use in general worship and special evangelistic meetings #184

- MIDI file from Make Christ King: a selection of high class gospel music for use in general worship and special evangelistic meetings #186

- MIDI file from New Songs of Praise and Power 1-2-3 Combined #290

- Audio recording from Revival Hymns and Choruses #173

- MIDI file from Revival Melodies #76

- Audio recording from Small Church Music #455

- Audio recording from Small Church Music #455

- MIDI file from Songs of Gladness for the Sabbath School #151d

- Audio recording from Sing Joyfully #300

- MIDI file from Sing Joyfully #300

- Audio recording from Trinity Hymnal (Rev. ed.) #253

- MIDI file from Timeless Truths #1086

- Audio recording from The Worshiping Church #467

- MIDI file from The United Methodist Hymnal #622

- MIDI file from Worship and Rejoice #256

My Starred Hymns

My Starred Hymns