Author (attributed to): Thomas á Kempis

Thomas of Kempen, commonly known as Thomas à Kempis, was born at Kempen, about fifteen miles northwest of Düsseldorf, in 1379 or 1380. His family name was Hammerken. His father was a peasant, whilst his mother kept a dame's school for the younger children of Kempen. When about twelve years old he became an inmate of the poor-scholars' house which was connected with a "Brother-House" of the Brethren of the Common Life at Deventer, where he was known as Thomas from Kempen, and hence his well-known name. There he remained for six years, and then, in 1398, he was received into the Brotherhood. A year later he entered the new religious house at Mount St. Agnes, near Zwolle. After due preparation he took the vows in 1407, was priested in 1413,…

Go to person page >Translator: Benjamin Webb

Benjamin Webb (b. London, England, 1819; d. Marylebone, London, 1885) originally translated the text in eight stanzas, although six only appear in Lift Up Your Hearts. It was published in The Hymnal Noted (1852), produced by his friend John Mason Neale. Webb received his education at Trinity College, Cambridge, England, and became a priest in the Church of England in 1843. Among the parishes he served was St. Andrews, Wells Street, London, where he worked from 1862 to 1881. Webb's years there coincided with the service of the talented choir director and organist Joseph Barnby, and the church became known for its excellent music program. Webb edited The Ecclesiologist, a periodical of the Cambridge Ecclesiological Society (1842-1868). A co…

Go to person page >Scripture References:

st. 1 = Eph. 3:18-19, Phil. 2:7

st. 2 = Matt. 3:13, Matt. 4:1-11

st. 3 = John 17:9

st. 4 = Rom 4:25, 1 Pet. 2:24

st. 5 = Rom. 8:34, John 16:7, 13

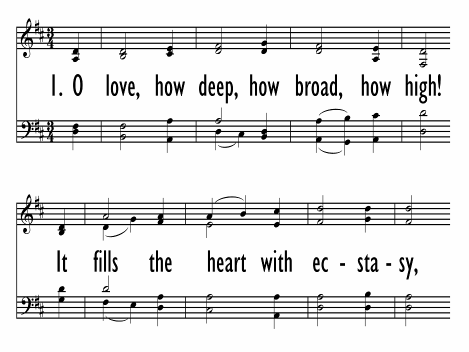

The original anonymous text in Latin ("O amor quam ecstaticus") comes from a fifteenth-century manuscript from Karlsruhe. The twenty-three-stanza text has been attributed to Thomas à Kempis because of its similarities to writings of the Moderna Devotio Movement associated with à Kempis. (that movement was an important precursor of the Reformation in the Netherlands). However, there is insufficient proof that he actually wrote this text.

Benjamin Webb (b. London, England, 1819; d. Marylebone, London, 1885) translated the text in eight stanzas. It was published in The Hymnal Noted (1852), produced by his friend John Mason Neale (PHH 342). Webb received his education at Trinity College, Cambridge, England, and became a priest in the Church of England in 1843. Among the parishes he served was St. Andrews, Wells Street, London, where he worked from 1862 to 1881. Webb's years there coincided with the service of the talented choir director and organist Joseph Barnby (PHH 438), and the church became known for its excellent music program. Webb edited The Ecclesiologist, a periodical of the Cambridge Ecclesiological Society (1842-1868). A composer of anthems, Webb also wrote hymns and hymn translations and served as one of the editors of The Hymnary (1872).

The text has a wide scope, taking in all of Jesus’ incarnate life: his birth (st. 1); identification with human affairs (st. 2); daily ministry (st. 3); crucifixion (st. 4); resurrection, ascension, and gift of the Spirit (st. 5); the final stanza is a doxology (st. 6). Thus the text summarizes Christ's life in the same manner as the Apostles' Creed. A striking feature is the text's emphasis on the fact that Jesus accomplished all of this "for us"; "for us" occurs at least a dozen times! The redemptive work of Christ is very personally, very corporately applied.

Liturgical Use:

Epiphany, especially later in the season; Lent, Holy Week, Easter, Ascension, and at many other times; the final stanza makes a good doxology for Epiphany, Lent, or the Easter season.

--Psalter Hymnal Handbook

Notes

Scripture References:

st. 1 = Eph. 3:18-19, Phil. 2:7

st. 2 = Matt. 3:13, Matt. 4:1-11

st. 3 = John 17:9

st. 4 = Rom 4:25, 1 Pet. 2:24

st. 5 = Rom. 8:34, John 16:7, 13

The original anonymous text in Latin ("O amor quam ecstaticus") comes from a fifteenth-century manuscript from Karlsruhe. The twenty-three-stanza text has been attributed to Thomas à Kempis because of its similarities to writings of the Moderna Devotio Movement associated with à Kempis. (that movement was an important precursor of the Reformation in the Netherlands). However, there is insufficient proof that he actually wrote this text.

Benjamin Webb (b. London, England, 1819; d. Marylebone, London, 1885) translated the text in eight stanzas. It was published in The Hymnal Noted (1852), produced by his friend John Mason Neale (PHH 342). Webb received his education at Trinity College, Cambridge, England, and became a priest in the Church of England in 1843. Among the parishes he served was St. Andrews, Wells Street, London, where he worked from 1862 to 1881. Webb's years there coincided with the service of the talented choir director and organist Joseph Barnby (PHH 438), and the church became known for its excellent music program. Webb edited The Ecclesiologist, a periodical of the Cambridge Ecclesiological Society (1842-1868). A composer of anthems, Webb also wrote hymns and hymn translations and served as one of the editors of The Hymnary (1872).

The text has a wide scope, taking in all of Jesus’ incarnate life: his birth (st. 1); identification with human affairs (st. 2); daily ministry (st. 3); crucifixion (st. 4); resurrection, ascension, and gift of the Spirit (st. 5); the final stanza is a doxology (st. 6). Thus the text summarizes Christ's life in the same manner as the Apostles' Creed. A striking feature is the text's emphasis on the fact that Jesus accomplished all of this "for us"; "for us" occurs at least a dozen times! The redemptive work of Christ is very personally, very corporately applied.

Liturgical Use:

Epiphany, especially later in the season; Lent, Holy Week, Easter, Ascension, and at many other times; the final stanza makes a good doxology for Epiphany, Lent, or the Easter season.

--Psalter Hymnal Handbook

Hymnary Pro Subscribers

Access

an additional article

on the Canterbury Dictionary of Hymnology:

Hymnary Pro subscribers have full access to the Canterbury Dictionary of Hymnology.

Subscribe now

My Starred Hymns

My Starred Hymns